From Next Avenue and 60 Minutes – By Laurence J. Kotlikoff and Terry Savage –

Alarming clawback letters, erroneous benefits calculations and overworked and undertrained call-center workers leave many retirees fuming.

Here’s a shocking fact about Social Security: It often makes huge mistakes in calculating our Social Security benefits. Even worse, it can take years for the agency to discover its own mistakes.

But once this happens, the bureaucracy offers no apology, shows no remorse. Instead, its computers start firing off menacing clawback letters demanding immediate repayment under threat of recouping their mistakes by taking the money out of workers’ future benefits.

If you don’t repay, your Social Security checks stop coming, just as threatened.

These clawback demand letters can arrive literally 20 years after you began receiving benefits. They can demand repayment of a few hundred dollars or many thousands of dollars. We’ve heard from people who were told they must repay as much as $300,000.

No explanations, just threats

The clawback letters are hard as nails and as cold as ice. There is no “we’re sorry.” Indeed, there is no information whatsoever as to the specific mistake and its cause. The letters simply say: You were overpaid, and you must repay $X by date Y.

But with no information whatsoever about the alleged mistake, how does one know if the mistake is not, itself, a mistake? Moreover, mistakes can happen in both directions. We’ve seen how doggedly Social Security works to recover overpayments. But does it work as hard to find underpayments? Indeed, how do any of us know we are receiving the correct amount in our monthly check?

In 2018, Social Security’s own Inspector General reported that the system had defrauded some 13 million widows and widowers out of $132 million. The Inspector General instructed the agency to identify its victims and pay them what was owed. To date, not a single defrauded widow or widower has received a penny.

The belated clawback letters can literally mean the difference between a comfortable retirement and financial anxiety. Here’s what a reader named Ruth posted on the AskTerry blog on her website.

“In May 2021 I received a letter from Social Secretary stating I owe $88,734 because I was not entitled to my husband’s benefits because I collect a pension. I went through all the process with the SS office, brought in all documents that were needed by them and nothing was ever told to me by them that I was not able to collect. I filed an appeal but never heard from them until now.

“I am 73 and had a heart attack with triple bypass done. I don’t want to lose my house! I have all the documents since this began almost two years ago. With COVID they never would get back to me and offices were always closed. Now they are threatening me. Please help!”

(If you have a Social Security horror story, please share it with Terry via her website. We post these stories on the digital platform Substack.)

More like Social Insecurity

As our growing list of horror stories shows, Ruth is far from alone. Our most vulnerable older adults are being harassed and threatened by Social Security, after relying on this agency to calculate their well-deserved benefits.

Six weeks back, we asked Social Security’s Chicago office to tell us how much money they are trying to get back, and how many individuals are receiving these letters. They have yet to respond, apart from saying, “We’re working on it.”

The answer to the scope of this problem may be found tucked away in Social Security’s annual trustees report. Its balance sheet includes a shocking $8.6 billion in receivables that “consists mainly of money due to SSA from SS and disability beneficiaries who received benefits in excess of their entitlement.”

Call for help that never comes

Yes, they’re trying to collect $8.6 billion in overpayments. If you divide that by what may be the average clawback amount, roughly $10,000, it suggests that about 800,000 of our most vulnerable citizens — including retirees, disabled workers, young children, disabled children, widows and widowers, divorced spouses and elderly parents — will be bullied into paying for Social Security’s mistakes.

When these clawback letters arrive, people naturally call Social Security. This can mean they will sit for hours on hold, only to have a phone representative eventually say they have no idea what happened. They literally cannot explain the specific mistake they made to cause this repayment demand.

Generally, folks are told they can appeal the clawback, but it’s hard to prepare an appeal when you don’t know the “crime.” Also, clawback waivers appear to be based on your having no other means of support. Even then, Social Security may only waive a portion of the clawback.

We have noticed that many issues arise from a miscalculation of the Windfall Elimination Provision, or WEP, which reduces Social Security benefits for people with “non-covered pensions” (typically government employees), but also qualify for Social Security benefits based on other jobs that were covered by Social Security.

Pay for mom’s mistake

But then there’s this:

“My son, who is now 25, has Social Security after him for a disability claim made by my ex-wife 20 years ago. (He was, of course, age 5 at the time!) They claim he must repay the $5,000 that was paid out to her. They are being aggressive in the pursuit. Is there anything he can do?”

Frankly, we have never heard of such an egregious abuse of power. It’s time for everyone in government, starting with the President, the chief trustee of Social Security, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, members of Congress and Social Security’s Acting Commissioner, Kilolo Kijakazi, to sit down and fix this mess. For these older adults, time is truly money.

Laurence J. Kotlikoff: Laurence Kotlikoff is a co-author of “Get What’s Yours from Social Security” and a professor of economics at Boston University. Read More

Terry Savage: Terry Savage is the author of “The Savage Truth on Money” and syndicated personal finance columnist. Read More

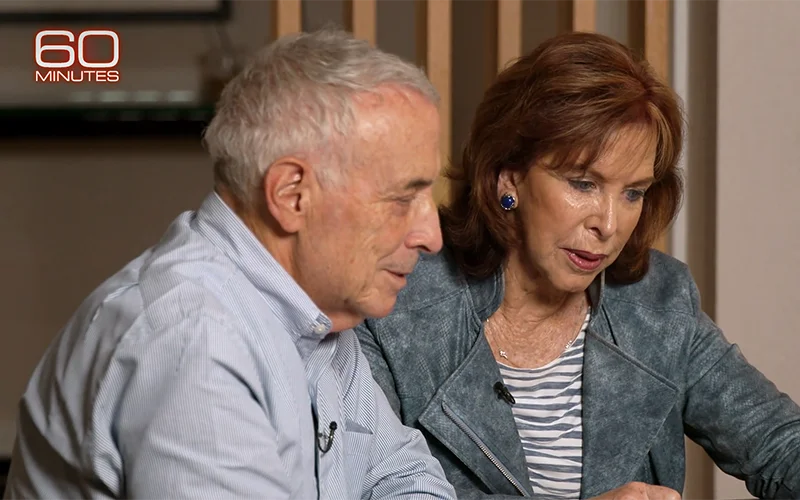

60 Minutes Nov. 5 article on the ‘clawbacks’: